We can’t have a fairy tale blog without first establishing what a fairy tale is. More specifically, what makes up a fairy tale? What makes it different than other stories?

If you do a quick Google search on the “ingredients” of a fairy tale you’ll find a pretty generic recipe pretty quickly. Everyone is quick to list off that fairy tales usually begin “once upon a time,” usually involve magic, and always have a happily ever after.

This is generally true. Generally. There will always be exceptions to these rules. One needs only look at Hans Christian Andersen’s original “The Little Mermaid” or his “The Little Match Girl” to know that not all fairy tales end so happily. And there do exist fairy tales without hints of magic, such as “The Boy Who Cried Wolf.”

However, most tales tend to follow that very simple formula. One thing you can almost always count on, especially with fairy tales told in English, is that they begin “once upon a time,” or use a similar variation. In fact, starting a story this way dates all the way back to that famous storyteller, Chaucer. One of his Canterbury Tales, specifically the Knight’s Tale, begins “once on a time.” Since then it’s been sighted in multiple English tales, again and again, so much so that today we recognize the phrase immediately and couldn’t tell you where we first heard it.

Is that famous beginning the only thing we need to call something a fairy tale? Not necessarily. Though it is a big part of the tradition, there are a few other elements I believe are necessary to define a fairy tale from, say, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, which does use a similar beginning (“Not so long ago, in the mysterious land of Toronto, Canada…”).

So what, then, are the ingredients to a tried and true fairy tale? After much consideration and lots of reading fairy tales throughout the years of my life, I’ve finally hit on what I believe is a pretty effective recipe for the perfect, stereotypical fairy tale.

Pretty simple right? Like any good story, you need your good and bad characters and some kind of obstacle to overcome. Fairy tales are also pretty short and involve that timeless beginning and elements of magic. But one of the biggest things about a fairy tale that makes it a fairy tale (and not Scott Pilgrim vs The World) is that it’s often retold again and again.

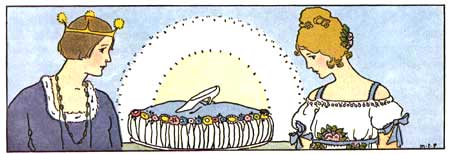

You can easily identify elements from this recipe in almost any fairy tale from multiple cultures. Want an example? Let’s use Cinderella, possibly the oldest and most well-known fairy tale in the world. We’ll use Charles Perrault’s version of Cinderella, which is closely reproduced in the Disney versions most of us know — though there are many variations to choose from!

The story opens similarly, with most translations simply starting, “Once there was…” We’re introduced to the heroine, Cinderella, and the villain, her own stepmother. Cinderella wants to go to the ball, but her stepfamily taunts her and leaves her behind. This obstacle is overcome by the arrival of a magical fairy godmother, who transforms Cinderella and sends her off to the ball in her pumpkin-turned-carriage. The story does have a happy ending, and Charles Perrault happens to end all his stories with a moral or two written in. In this case, it can be succinctly summed up like this:

Young women, in the winning of a heart, graciousness is more important than a beautiful hairdo.

Cendrillon, Charles Perrault

Granted, Perrault assigned morals to his particular stories that can be a little hard to swallow in modern times, but that is a post for another day.

The point I’m trying to make is that the formula or recipe for a fairy tale is fairly straight-forward. And it’s so deeply ingrained in the stories we all know that we don’t even notice the same formula is being used. Or if we do, we recognize it as a unique narrative form. Like recognizing the difference between a epic poem and a free verse poem, or between a science fiction novel and modern-day romance novel.

One of the reasons fairy tales endure so much today is that it’s easy to take this formula and come up with a new fairy tale. They were originally told aloud, rather than read on a printed page, and anyone who’s played a game of Telephone knows how a story changes when passed to other people.

But while little things have changed, the formula didn’t. There’s a sort of comfort in knowing how a tale will progress. There’s a certain allure to the magical and fantastical elements found in the story.

At the same time, it’s thrilling to see how these stories are twisted and retold in new and different ways. It’s the very nature of fairy tales to be retold and changed to suit the whims of the teller or the audience. There are hundreds of different Cinderella stories across dozens of cultures and centuries of storytellers to prove this point. We’re still making Cinderella stories today.

We’re just not done with fairy tales. Whether we make another Cinderella, or come up with the stepmother’s side of the story, there are countless ways you can take a fairy tale and make it your own. That’s sort of what fairy tales are all about. And probably why retellings are still popular today.

There might be hundreds of versions of the same fairy tale out in the world. But who’s to say we can’t use one or a dozen more?

Little Mermaid picture from: Gutenberg.org: Stories from Hans Andersen, with illustrations by Edmund Dulac, London: Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd., 1911.

Cinderella Picture from: SurLaLuneFairyTales.com: Bates, Katharine Lee, editor. Once Upon a Time: A Book of Old-Time Fairy Tales. Margaret Evans Price, illustrator. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1921.

Quote from Cendrillon: Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., ca. 1889, pp. 64-71.

Recipe card made by me. Feel free to share!