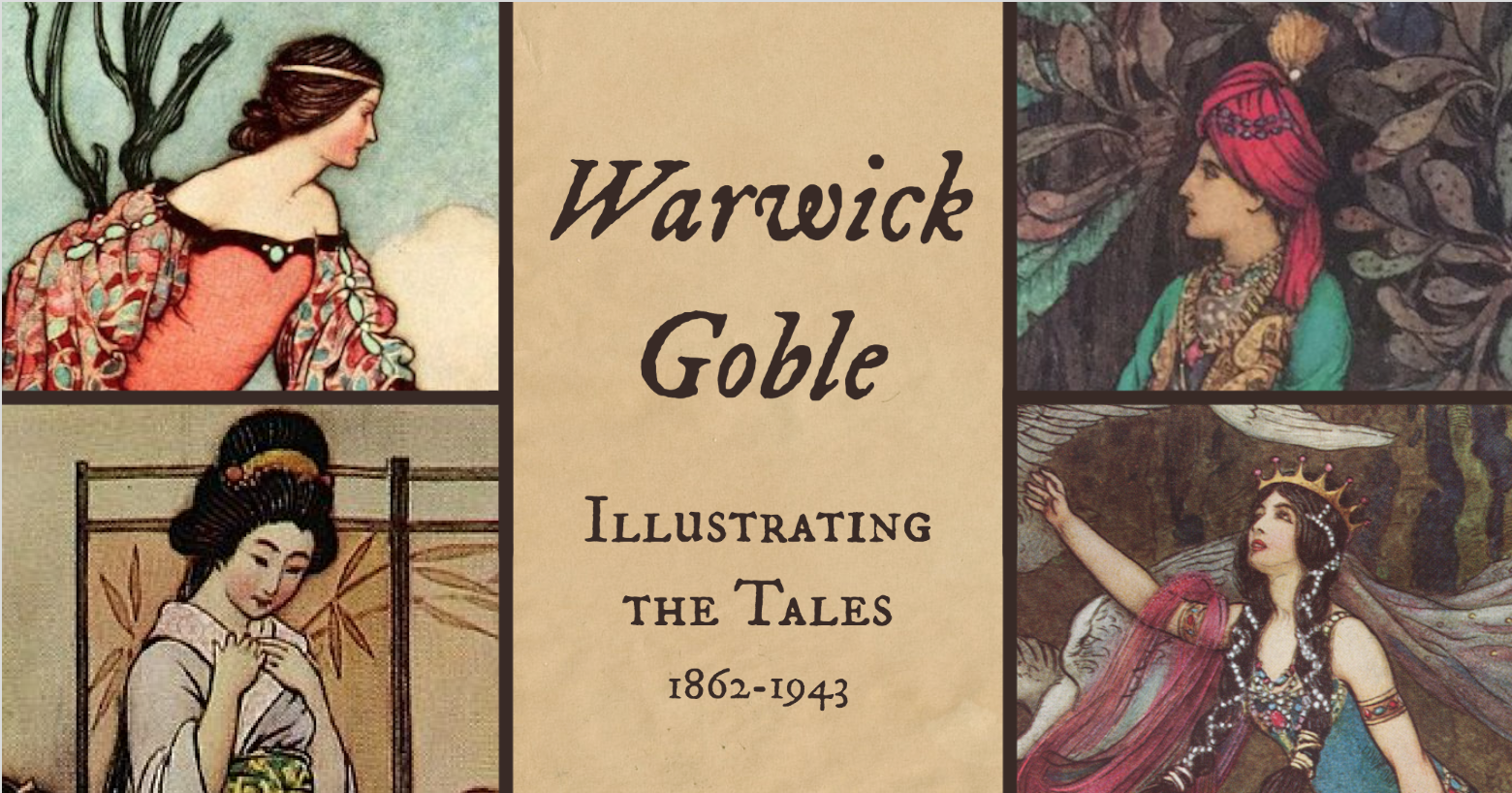

Fairy tale artwork can be some of the most beautiful or most terrifying artwork out there, especially when certain art styles meet certain dark, creepy, or downright strange fairy tales. But I have a soft spot for the softer, prettier types of artwork that often gets included alongside fairy tales. You know, the ones that have all the colors and everyone looks so youthful and magical?

Warwick Goble’s artwork is exactly like that.

Warwick Goble is, I think, probably my all-time favorite fairy tale artist, although I will admit that he does have to compete with Edmund Dulac and Arthur Rackham. But unfortunately for Rackham, his artwork can get a little creepy, and though Dulac and Goble use similar art styles, Goble’s command of watercolor just shines more vibrantly.

In fact, I like Goble’s artwork so much that in honor of having to upgrade my phone after 5 years of avoiding upgrades, I went ahead and ordered a custom case that would showcase his work. Because why not? Everything, more or less, is in the public domain, which means we all have easy access to enjoy his gorgeous work.

So without further ado, let’s take a look at some of my favorite pieces by Warwick Goble.

Warwick Goble was born on November 22nd, 1862 in North London, England. He studied first at the City of London School and then went on to study art at the Westminster School of Art. At the start of his career, he produced sketches and illustrations for news articles, magazine articles, and short stories, first in the Westminster Gazette and Pall Mall Gazette, and then later in The Boy’s Own Paper, Strand Magazine, and Pearson’s Magazine. His illustrations for H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds first appeared in Pearson’s Magazine, where the novel was serialized, and then included in the first publication of the work as a novel.

But we’re going to skip Goble’s illustrations of martians and spacecraft because, well…they were kind of bad. So bad, in fact, that in a second, revised publication of the novel, H.G. Wells actually takes a dig at Goble.

I recall particularly the illustration of one of the first pamphlets to give a consecutive account of the war. The artist had evidently made a hasty study of one of the fighting-machines, and there his knowledge ended. He presented them as tilted, stiff tripods, without either flexibility or subtlety, and with an altogether misleading monotony of effect. The pamphlet containing these renderings had a considerable vogue, and I mention them here simply to warn the reader against the impression they may have created. They were no more like the Martians I saw in action than a Dutch doll is like a human being. To my mind, the pamphlet would have been much better without them.

H.G. Wells, Book II – The Earth Under the Martians; Chapter II – What We Saw from the Ruined House

Ouch, right? But Goble’s illustrations for Pearson’s Magazine were done years before he began to settle into the art style that I love him for. War of the Worlds was serialized in 1897 and published as a novel in 1898. By 1907, the public was much more interested in novels and story collections with full color illustrations, thanks to Rackham’s illustrations for J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, and Dulac’s illustrations in Laurence Houseman’s version of Arabian Nights. Goble picked up the trend too, first by doing full color illustrations for Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies and then, in 1910, forty illustrations for a collection called Green Willow and Other Japanese Fairy Tales, collected and published by Grace James.

It’s thought that Dulac either influenced Goble, or that they both studied the same type of Japanese-style art to produce their illustrations, although I can’t find anywhere that states what the art style is called or if they were both just influenced by Japanese art styles generally. Nevertheless, Goble continued to use Asian-inspired techniques to provide illustrations for other Asian-inspired works, such as Folk Tales of Bengal by Rev. Lal Behari Day.

He also did the illustrations for Indian Myth and Legend and Indian Tales of the Great Ones. But the illustrations I know him best for are the European fairy tales I read as a child, although I didn’t encounter his artwork until later in life.

Goble had done illustrations for Tales from the Pentamerone, but the majority of my favorite illustrations come from his work in Dinah Craik’s The Fairy Book, published in 1913. You might recognize his “Little Red Riding Hood” artwork, here to the left. Another favorite, down below, is the piece he did for “Beauty and the Beast.” He made the curious decision to give the Beast the heard of a boar, but it’s still one of my favorite illustrations of that story.

Less known are these next two tales, but the artwork for them is still lovely. I just love Goble’s use of watercolors. Pink, teal, light blue, mint green, I enjoy all of these colors normally and they just pop when presented in these illustrations. First is this piece for “The Iron Stove” which is, as I just recently learned myself, a Brothers Grimm variation on a “Cupid and Psyche” tale, like the Norwegian “King Valemon” or “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.”

Actually, this is the image I decided to use for my phone case, even though the story was so new to me. I just loved the colors!

Second is from the Brothers Grimm story “The Six Swans” in which a sister must save her six brothers after they have been turned into swans. This story is actually starting to gain a bit of traction for fairy tale retellings. R.C. Lewis, who wrote Stitching Snow, which I reviewed last Saturday, actually retold the Hans Christian Andersen version of this story in her novel Spinning Starlight, and I know of a couple other retellings as well.

Goble went on to do the black and white sketches for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, and soon after gave up his illustrating career to focus on sculling, cycling and traveling (as you do). He died in 1943 at his home in Surrey, leaving behind some of the loveliest fairy tale, fantasy, and folk tale artwork produced during the “Golden Age” of illustrated fairy tale publication. Though he isn’t as well known as Arthur Rackham or Edmund Dulac, his art continues to mesmerize me with its colors and beauty.

I hope you guys enjoyed this brief look at some of his work, which is just a fraction of the hundreds of plates, sketches, and full-color illustrations he completed and produced for published works over his lifetime. Keep checking back for more blog posts–you may get to glimpse work by Rackham and Dulac too, in time!